The Perfect Man Who Wasn’t

For years he used fake identities to charm women out of hundreds of thousands of dollars. Then his victims banded together to take him down.

By the spring of 2016, Missi Brandt had emerged from a rough few years with a new sense of solidity. At 45, she was three years sober and on the leeward side of a stormy divorce. She was living with her preteen daughters in the suburbs of St. Paul, Minnesota, and working as a flight attendant. Missi felt ready for a serious relationship again, so she made a profile on OurTime.com, a dating site for people in middle age.

Among all the duds—the desperate and depressed and not-quite-divorced—a 45-year-old man named Richie Peterson stood out. He was a career naval officer, an Afghanistan veteran who was finishing his doctorate in political science at the University of Minnesota. When Missi “liked” his profile, he sent her a message right away and called her that afternoon. They talked about their kids (he had two; she had three), their divorces, their sobriety. Richie told her he was on vacation in Hawaii, but they planned to meet up as soon as he got back.

A few days later, when he was supposed to pick her up for their first date, Richie was nowhere to be found, and he wasn’t responding to her texts, either. Missi sat in her living room, alternately furious at him (for letting her down) and at herself (for getting her hopes up enough to be let down). “I’m thinking, What a dumbass I am. He’s probably at home, hanging out with his wife and kids,” she says.

At 10 p.m., she sent him a final message: This is completely unacceptable. A few minutes later, she got a reply from Richie’s friend Chris, who said Richie had been in a car accident. He was okay, thank God, but the doctors wanted to do some extra testing, since he’d suffered head trauma while in Afghanistan. Chris sent Missi a picture of Richie in a hospital bed, looking a little banged up but grinning gamely for the camera. Missi felt a wave of relief, both that Richie was okay and that her suspicions were unwarranted.

When she finally did meet him in person, her relief was even more profound. Richie was tall and charming, a good talker and a good listener who seemed eager for a relationship. He could be a little awkward, but Missi chalked that up to his inexperience—he told her he hadn’t been with a woman in eight years. Plus, dating him was fun. Richie had a taste for nice things—expensive restaurants, four-star hotels—and he always insisted on paying. He kept a motorboat docked at a nearby marina, and he’d take Missi and her daughters out for afternoons on the water. The girls liked him, and so did the dog. Richie mentioned that his cousin Vicki worked for the same airline as Missi. The two women didn’t work together regularly, but they knew each other. Missi thought it was a fun coincidence. “Don’t mention us to her,” Richie said. “One day we’ll show up together to some family event and surprise her; it’ll be great.”

A few months into their relationship, she missed a shift at work and got fired. Richie leaped into provider mode. He told her that he’d take care of her bills for the next four months, that she should relax and take stock of her life and spend time with the kids. Maybe he could put her and the girls on his university insurance. Maybe, he told her, with the benevolent confidence of a wealthy man, she wouldn’t have to work. The offer wasn’t all that appealing to Missi—“I didn’t want to be a stay-at-home mom again,” she says—but she took it as a sign that things were getting serious.

The longer they kept dating, though, the more problems cropped up. Richie liked to say he didn’t “do drama,” but drama seemed to follow him nonetheless. It got to feel as if every text from him was an announcement of some new disaster: He had to check his daughter Sarah into rehab; he had to put his beloved shih tzu, Thumper, to sleep. Richie had lingering medical problems from his time in the service, and Missi was constantly having to drop him off at or pick him up from the hospital. He was always canceling plans, or not showing up when he was supposed to. When Missi got fed up—Why did I get out of a crappy marriage just to be in this crappy relationship?—some new tragedy would happen (his mother died; he was in a motorcycle accident), and she’d be roped back in.

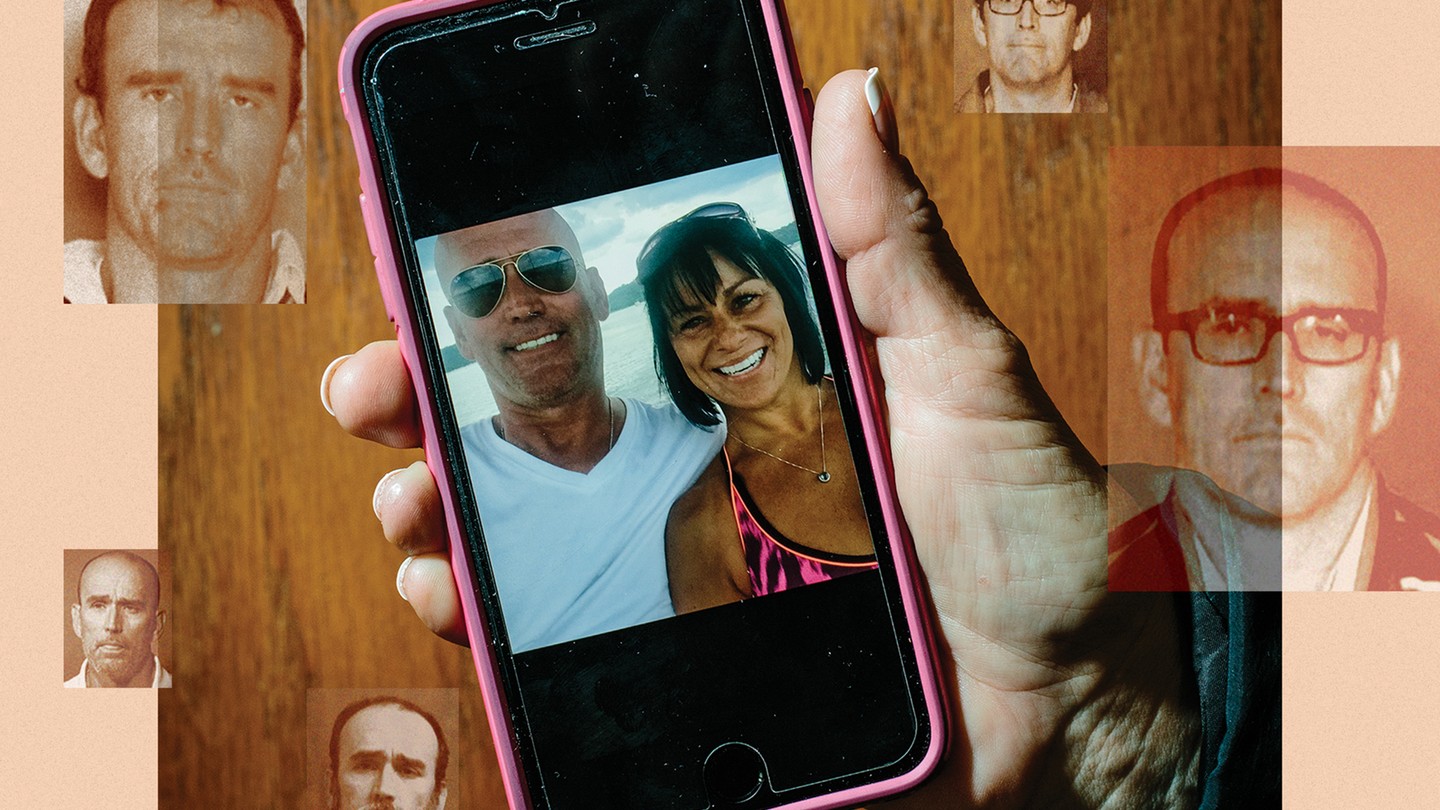

One day in early August, driven by a feeling she couldn’t quite pinpoint, Missi took a peek at Richie’s wallet. Inside was a Minnesota state ID with a photograph that was unmistakably Richie’s, but with an entirely different name: Derek Mylan Alldred. The wallet also contained a couple of credit cards belonging to someone named Linda. Missi’s heart sank. She’d had a nagging sense that something wasn’t right in her relationship, but she’d shaken it off as her being untrusting. These mysterious objects in his wallet, though, seemed to affirm that Richie was engaged in some larger form of deceit, even if she didn’t understand all the details just yet.

When Missi googled Derek Alldred, half a dozen mug shots of Richie—Derek—popped up, alongside news articles with alarming phrases such as career con man and long history of deception. Missi sat down on the couch and slowly read every word of every article she could find: Derek Alldred had posed as a firefighter and scammed hospitals out of drugs. Derek Alldred had dated a woman in California under false pretenses and drained her bank account of almost $200,000. Derek Alldred had married a woman, pretended to pay the bills on their home, then vanished after it was foreclosed on. Derek Alldred had posed as a surgeon, checked into the posh Saint Paul Hotel with a woman and her two daughters, racked up nearly $2,000 in charges, then skipped out on the bill (and the woman).

As she read, Missi began to feel sick, as if her body was having trouble physically assimilating the idea that her boyfriend was not a scholar and war hero, but rather a serial con man. And those credit cards kept nagging at her: “There is someone else out there who is being completely fricking screwed right now,” she remembers thinking. It took a bit of detective work, but eventually Missi tracked Linda down on Facebook and sent her a message. “You’re probably going to think I’m crazy,” it began.

When Linda Dyas, age 46, got Missi’s message, she was in the house she shared with Rich Peterson, her boyfriend of seven months. Linda, who is tall and blond and funny, had been going through an ugly divorce when she’d met Rich on OurTime.com, and he’d seemed almost too good to be true: a Christian, a military vet, a fellow conservative. On their first date, after the server set down their plates, Rich closed his eyes and said a beautiful prayer. “I was blown away by that,” Linda told me when we met at a wine bar in St. Paul over the summer. “Here I was on a first date, and he’s actually going to stop and say a prayer in a restaurant. It was touching.” Linda was smitten. “Head over heels, you know?” she said. “Within two weeks, he was at my house all the time.”

After a few months, Linda lost her job with a financial-services company, but Rich made it seem okay. He found them a house to rent in an upscale suburb of St. Paul, one she wouldn’t have been able to afford on her own, and she and her 6-year-old son moved in. Linda hung her clothes next to Rich’s Navy uniforms; he displayed the framed certificates for his military honors—a Purple Heart, a Silver Star—on the walls. One day she stumbled onto paperwork for a $100,000 college fund he had secretly started for her son, and her heart surged.

Recently, though, the relationship had been rockier. Rich drank a lot, and his constant trips to the hospital—which he blamed on the persistent effects of his war wounds—were exhausting. When Linda received Missi’s message, she initially dismissed it as the rantings of a jealous ex. But for a few weeks she’d had a vague sense that things between her and Rich were askew in some fundamental way. When, a couple of days later, she finally opened the links Missi had sent, she realized why. “My first instinct was How do I get him out of the house?” she recalled. He solved that problem for her, announcing that he was once again in so much pain, he needed to go to the emergency room. Linda dropped him off and then called the police on her way home. She sat up for hours. At three in the morning, Derek told her he would catch an Uber home, and Linda alerted the police. When she saw the red-and-blue lights through her window, she sent Missi a message, letting her know that Derek was in custody.

Linda eventually figured out that Derek Alldred had not only been lying about his name, his job, and his past—he’d been depleting her savings to bolster his fake life. As she went over her bank statements, she said, she began to piece it together: how he had stolen her emergency credit cards out of her jewelry box and ordered new cards in her name, then used those cards to fund fancy dinners and trips to Hawaii with her and other women; how he’d siphoned money from her retirement savings to pay off the credit-card bills, and to buy a boat and two motorcycles he’d ostensibly given her as gifts; how he’d ask her to drop him off at the hospital, only to get Missi to pick him up as soon as she was gone; how her name was somehow the only one on the house’s lease, and she was now on the hook for rent she couldn’t afford.

The night after Derek’s arrest, Missi came over so Linda wouldn’t have to be alone. When Linda’s dog trotted into the room, Missi laughed. “Thumper!” she said. “I thought you were dead.” (Derek’s mother, they later learned, was also still alive.) On the surface, the two women didn’t seem to have much in common—Missi is grounded and easygoing, with a yin-yang symbol tattooed on her big toe, while Linda is a conservative Navy vet with a drawl that betrays her Texas roots—but they bonded over the absurdity of their shared situation.

The next day, Washington County police were at Linda’s house taking her statement when a delivery arrived, addressed to Rich Peterson. Linda handled the package gingerly; it felt like a missive from an alternate reality. One of the police officers told her she might as well open it: “It’s not like he’s a real person.” The box contained whiskey and chocolate and a sweet get-well-soon note from a woman whose return address was just a few neighborhoods away.

Linda texted Missi, who compiled a dossier of news articles documenting all of Derek’s misdeeds and dropped it off with the third woman, Joy (who asked to be identified by her middle name). That weekend, Joy stopped by Linda’s, and the two women split a bottle of wine, trying to piece together how they’d been taken so thoroughly. Joy, a 42-year-old IT director, had also met “Rich” on OurTime.com, in February. He’d told her he was a professor who volunteered at a homeless shelter downtown. (The women later found out that he had actually been living at the shelter before he moved in with Linda.) They’d dated for a few months, until “he started having just a ton of drama in his life,” Joy says. She broke it off with him but stayed friendly. On the Fourth of July, he sent her a picture of himself looking tan and happy, his arms around Missi and her kids on the boat that Linda had paid for. I bought a boat and took my sister and her kids out on it today, he wrote. My life has calmed down, want to try again? Joy decided to give him another chance. She later found that he’d stolen almost $8,000 worth of jewelry, her passport, and her birth certificate.

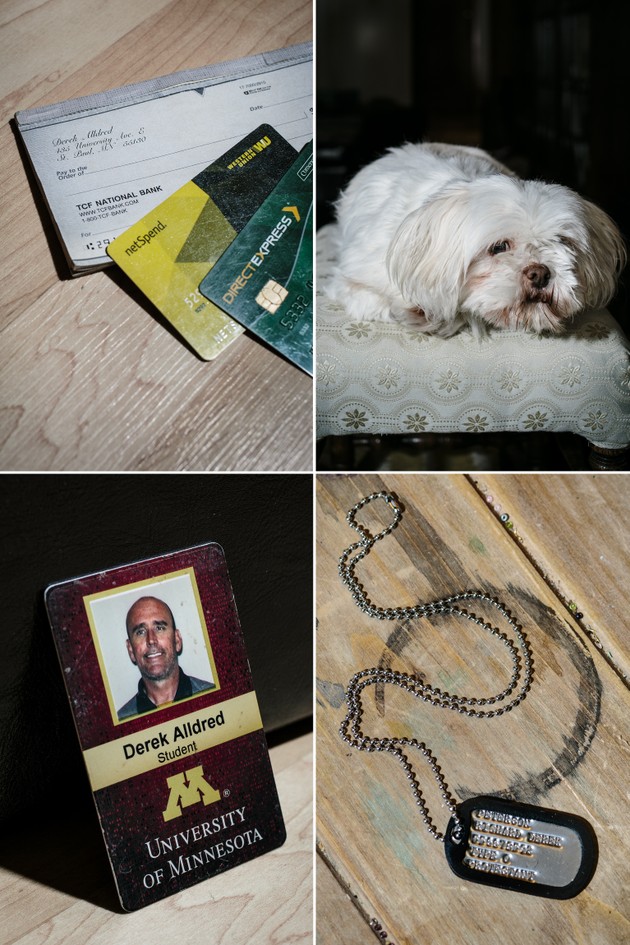

The false life that Derek—it was still hard not to slip and call him Rich—had constructed for himself was thorough: He had a University of Minnesota email address and an ID card that allowed him to swipe into university buildings. He would FaceTime the women from UM classrooms between classes. He had hour-long phone conversations—ostensibly with his admiral, his faculty supervisor, or his daughter Sarah, three people who turned out not to exist—during which Linda could hear a voice on the other end of the line. He had uniforms and medals and a stack of framed, official-looking awards: a Purple Heart and a Silver Star, a seal Team One membership, a certificate of completion for a naval underwater-demolition course. There were just so many props bolstering Derek’s stories that even when doubts had started to bubble up, the women had repressed them—there’s no way it could all be fake, they’d told themselves. That would be crazy.

The three women’s conversations had another recurring theme: “We also knew there had to be more victims,” Linda told me.

Americans love a con man. In his insouciance, his blithe refusal to stick to one category or class, his constant self-reinvention, the confidence man (and he is almost always a man) takes one of America’s foundational myths—You can be anything you want to be!—to its extreme. The con man, the writer Lewis Hyde has argued, is “one of America’s unacknowledged founding fathers.”

Con men thrive in times of upheaval. “Transition is the confidence game’s great ally,” Maria Konnikova writes in The Confidence Game, an account of how swindlers manipulate human psychology. “There’s nothing a con artist likes better than exploiting the sense of unease we feel when it appears that the world as we know it is about to change.” The first great era of the American scam artist—the period when the confidence man got his name—began in the mid-19th century. The country was rapidly urbanizing; previously far-flung places were newly linked by railroads. Americans were meeting more strangers than ever before, and thanks to a growing economy, they had more money than previous generations. All of those strangers, all of that cash, resulted in an era powered by trust, one that Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner satirized in The Gilded Age for its “unlimited reliance upon human promises.”

The age of the internet, with its infinitude of strangers and swiftly evolving social mores, has also been good for con men. The FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center, which tracks internet-facilitated criminal activity, received nearly 300,000 complaints in 2016, reporting total losses of more than $1.3 billion. Of those, more than 14,500 were for relationship fraud, a number that has more than doubled since 2011. In 2016, relationship scams were the second-most-costly form of internet fraud (after wire fraud), netting scammers nearly $220 million. By comparison, Americans lost only $31 million to phishing scams, about $2.5 million to ransomware attacks, and $1.6 million to phony charities.

The FBI warns that the most common targets of dating scams “are women over 40 who are divorced, widowed, and/or disabled.” In many cases, women are courted online by men who claim to be deployed in Afghanistan or tending an offshore oil rig in Qatar. After weeks or months of intimate emails, texts, and phone calls, the putative boyfriend will urgently need money to replace a broken laptop or buy a plane ticket home. Some, like Derek or “Dirty John” Meehan—whose romance scam was exposed last year by the Los Angeles Times—escalate an online relationship to an in-person con, going as far as living with their victims or even marrying them. Derek stands out for how remarkably prolific he was: He often had two or three separate relationship scams going at a time. When one woman discovered the truth, he’d quickly move on to another.

According to the Justice Department, only 15 percent of fraud victims report the crimes to law enforcement, largely due to “shame, guilt, embarrassment, and disbelief.” “You feel really crappy about yourself,” Missi told me, then slipped into a tone that sounded like the mean voice that lives inside her head: “I’m a stupid woman; I’m a dumb, dumb, dumbass.”

But Derek’s victims didn’t let their shame stop them from coming forward. Many of them did report him—only to discover that by drawing them so deeply into his con, he had paradoxically made it less likely that he’d face consequences.

The police released Derek after 48 hours, telling Linda they wanted to build a stronger case. (A police spokeswoman told me the county attorney had concluded that fraud charges probably wouldn’t have held up in court. Because Linda’s and Derek’s lives were so entwined, it would have been too difficult to determine which credit-card charges were fraudulent and which were authorized.) Seven months later, the police department finally issued a warrant for Derek’s arrest, on one misdemeanor charge of impersonating an officer. By then he was long gone.

While Linda sorted through her finances, her sister-in-law delved into old news articles about Derek, looking for any information that might be useful in bringing him to justice. Most of the women quoted were anonymous, or referred to only by their first name. A woman named Cindi Pardini, however, had used her full name. A tech professional living in San Francisco, she said Derek had stolen hundreds of thousands of dollars (and 660,000 airline miles) from her over the course of a few months in 2013. Linda sent Cindi a Facebook message, and soon learned that Cindi was a kind of unofficial point person for Derek’s accusers. Because her name was one of the only searchable ones linked to his, women who’d been scammed by Derek reached out to Cindi through Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn. She was in touch with about a dozen victims.

Cindi wasn’t always easy to deal with. On the phone with the other victims, she’d ramble for hours about Derek and the trouble he’d brought into her life, how he’d drained her bank account, ruined her credit score, and undermined her sense of reality. “I was not in a good place,” Cindi admits. “This has taken over my life for the past five years. My friends and family are like, ‘Why are you still going after this? It’s killing you.’ ”

But Cindi’s single-mindedness also made her the case’s most diligent detective. She kept careful track of news reporting on Derek’s exploits and made sure police were informed. She also contacted Derek’s college-age daughter, who Cindi learned was estranged from her father. (The second daughter, Sarah, was a fabrication.) And she talked with one of his childhood friends, who said that Derek, who had grown up in a wealthy suburb of San Francisco, was trouble from an early age. He’d often discussed his family with Missi, and at least some of what he told her appears to have been true. “He’d talk about how they were such good people, and how he was such a black sheep in his family,” Missi says. Cindi was in touch with one of his earliest victims, a woman who had met Derek in the early 1990s and had been convinced that he was a medical student conducting important cystic-fibrosis research.

Cindi added Linda to a group text with several other victims, and Linda found some comfort in swapping stories with them, and in seeing that they were far from stupid. If anything, Derek seems to have preferred intelligent women; his victims included a doctor and a couple of women who worked in tech. Linda herself was an engineer at a nuclear-power plant. But the other women’s stories of trying to hold Derek to account for his crimes were not encouraging.

JoAnn, a 43-year-old from Minneapolis who asked that her last name not be used, met “Derek Allarad” on Match.com in August 2014. He told her he was a lawyer with a big downtown firm; in reality, he was hiding out from a warrant for defrauding the Saint Paul Hotel. Derek racked up about $23,000 on JoAnn’s credit cards during the three months they were together. When she reported him to the police, she was told that legal action would likely be a waste of her time and money. “The fraud detective told me it would cost me way too much money to get a lawyer and sue him in civil court,” JoAnn says. “He said they’d say I was just blaming my ex-boyfriend because I’m bitter. He said, ‘If I were you, I’d let it go.’ ” Six months and many phone calls later, the credit-card company finally reversed the charges. But JoAnn still regrets not taking Derek to court. “Just because of how many women he hurt since me,” she says.

All together, Derek seems to have scammed at least a dozen women out of about $1 million since 2010. He used different names and occupations, but the identities he took on always had an element of financial prestige or manly valor: decorated veteran, surgeon, air marshal, investment banker. Con artists have long known that a uniform bolsters an illusion, and Derek was fond of dressing up in scrubs and military fatigues. He tended to look for women in their 40s or 50s, preferably divorced, preferably with a couple of kids and a dog or two. Many of his victims were in a vulnerable place in their lives—recently divorced, fresh out of an abusive relationship, or recovering from a serious accident—and he presented himself as a hero and caretaker, the man who would step in and save the day. Even women who weren’t struggling when they met Derek soon found their lives destabilized by the chaos he brought—they lost jobs, had panic attacks, became estranged from family members.

Yet, as far as the growing group of Derek’s victims could ascertain, he had never been charged for a crime against any of the women he’d scammed, only for defrauding businesses. Derek seems to have counted on the fact that credit-card abuse is often not taken all that seriously by law enforcement when the victim and the perpetrator know each other. Even in instances where the police pursued Derek, he’d typically serve a short sentence. Or he’d just skip town—like he did in November 2014, after he was caught racking up thousands of dollars in fraudulent charges at luxury hotels. When he was finally captured and brought back to Minnesota, prosecutors lobbied to escalate the charges and hold him on $100,000 bail.

“That’s a little harsh, don’t you think?” the judge asked.

“Judge, if I may,” the assistant county attorney replied, “the defendant is a con man. He conned a number of victims within the state of Minnesota. He’s been all over the world pretending to be people he’s not, and taking money from people who don’t have money to spare.”

The judge denied the motion. About six months later, Derek was released. Shortly afterward—and despite the fact that his parole mandated that he stay in Minnesota—he was sitting on a beach in Hawaii with another woman who thought she’d met the perfect man.

For years, Derek had evaded punishment by moving around; local police had limited ability to chase him across state lines. But the women he’d victimized had no jurisdictional limitations. They began tracking his progress across the country, using social media to share updates and information—and to warn others.

Missi reached out to her former co-worker at the airline, Vicki, who was Derek’s cousin-in-law—that part of his story, at least, wasn’t a total lie. After Missi explained what Derek had done, Vicki agreed to pass on any information she learned. Through a family member, Vicki heard that Derek had left Minnesota and was hiding out with his mother in Sedona, Arizona—where, lo and behold, he had an outstanding warrant for an old DUI. Urged on by Missi, Vicki alerted the local police, who picked him up in early September 2016 and held him in the county jail for a few days. It wasn’t much, but the women took satisfaction in seeing him face at least some consequences.

Still, Derek had a remarkable ability to keep perpetrating the same scam. After his release for the DUI, he began dating a new woman, posing as Navy seal Richard Peterson. She soon discovered that he had stolen and pawned some of her jewelry. He was arrested, pleaded no contest, and was taken back to jail, but was bailed out and never showed up for his sentencing. By January 2017, he’d popped up in Las Vegas, where he met another woman and joined a country club, racking up charges before skipping town in April.

When new victims reached out to Cindi Pardini, she’d add them to the group text so they could share their stories with the other women. It was frustrating to find out about Derek’s latest escapades only after the damage had been done. His victims watched and waited, hoping he’d soon make a mistake that would take him out of action for good.

Consume enough media about scam artists and, strangely enough, you too might find yourself wanting to date one. In The Big Con, perhaps the seminal book on American con men, David Maurer calls them “the aristocrats of crime.” The writer and critic Luc Sante once wrote that “the best possess a combination of superior intelligence, broad general knowledge, acting ability, resourcefulness, physical vigor, and improvisational skills that would have propelled them to the top of any profession.” On film, they’re played with a spring in their step and a glint in their eye: Think Paul Newman in The Sting, Leonardo DiCaprio in Catch Me If You Can. The con man looks good in a suit and is in on the joke. (“Humor is never very far from the heart of the con,” wrote Sante.) And who doesn’t want to be in on the joke? Our appetite for stories about cons is, in part, a way of reassuring ourselves that we’d never be so foolish as to be taken. It’s in our own self-interest to dismiss the victims of a con as greedy (you can’t cheat an honest man, as the adage goes) or just plain dumb: If being scammed is somehow their fault, that means it couldn’t happen to us.

One excellent way to dispel yourself of any con-man fantasies, however, is to spend some time with the people they’ve hurt. Derek’s victims are negotiating ruined credit scores and calls from collection agencies. Several were so flattened by the experience, they’ve had old medical problems flare up or have struggled to go back to work.

“You just lose days,” Linda told me. She’d plastered her wall with sticky notes mapping out Derek’s crimes: “That’s what I was doing instead of looking for a job; instead of taking care of the motorcycle, the bank accounts, the bad checks. Instead of moving on with my life; instead of living.” Saddled with the rent for a house she couldn’t afford, she’d scraped together enough to pay for all but the very last month; now she has an eviction on her record. She and her son crashed on friends’ couches while she found a place to live, and, she told me, her ex-husband began campaigning for full custody of their son.

Even more damaging than the financial ramifications was the damage to their fundamental faith in the world, that bedrock sense that things are what they seem. “My mind was all over the place—Am I being taken or am I being overly suspicious?,” Derek’s Las Vegas victim, Kelly, recalls. “It’s so far-fetched—you’re just like, there’s no way. He gets into your life, your family’s life, your finances. I didn’t know that people like him existed.” The damage rippled outward, affecting the women’s family and friends as well: “It just about killed my mother,” Linda said. “He would sit and talk with her for hours. She’s like, ‘Was all of it a lie?’ ”

Many of the women I spoke with felt compelled to make the same point: that this wasn’t just a dating-scam story. They reminded me that Derek had scammed hospitals and insurance companies long before he began meeting women on dating sites, and that he’d conned many people beyond just 40-something divorcées. He won over their parents, friends, and co-workers; he convinced hotel clerks and Mercedes salesmen and bankers and real-estate agents and doctors. He was able to finagle country-club memberships and hospital admissions. He met actual Navy veterans, who took him at his word.

Derek’s victims kept underlining this point, I think, because they understood that crimes against women, particularly ones that happen in a domestic context, are often discounted. “It’s a he-said, she-said domestic fight” to the police, Linda said. “They lump it right in with divorce and family law.” She said an officer told her, “Well, it’s not like anyone got hurt; we have higher priorities.” They knew that some people hear dating scam and translate that to pathetic/desperate woman.

The implication is that these women should’ve known better, or perhaps that they’re complicit in their own victimization. If a woman reports her ex for stealing from her, who’s to say she’s not just brokenhearted and vindictive? Derek himself was happy to exploit such stereotypes; when his victims uncovered his real identity, he’d sometimes threaten to expose them as bad mothers or alcoholics, crazy women who couldn’t be trusted.

Even Derek’s victims, who understand better than anyone else how these things work, repeatedly questioned one another’s choices when speaking with me: How did she let it go on that long, why did she let him move in when she barely knew him, how did she not see through this or that obvious lie? It’s a testament to the persistent belief that cons always happen to someone else that women who had fallen for Derek Alldred’s schemes heard other victims’ very similar stories and thought, I never would have fallen for that.

For Missi and Linda, their crossed paths have resulted in the peculiar sort of friendship that can arise from shared trauma. Derek entwined their lives without their consent, taking Missi out on the boat he’d bought with Linda’s money; showing Missi photos of Linda’s son, his “nephew.” Initially, there was some slight underlying tension between the two women due to the fact that Derek hadn’t stolen any money from Missi, while he’d drained more than $200,000 from Linda’s retirement account. Joy had floated the theory that Missi was the one Derek “really” cared for, an idea that Linda dismissed out of hand: “That man is not capable of love.”

On a warm day last spring, I followed Linda over to Missi’s house, in the suburbs of St. Paul. We talked about Derek for four hours, dissecting his actions and puzzling over his motivations. Late in the evening, Linda told another wild part of the saga, involving a half-million-dollar house Derek was going to buy for them before the escrow money mysteriously went missing.

“You listen to Linda, and you’re like, ‘How did you take that at face value?,’ ” Missi said.

“I had my other stuff going on,” Linda said, a bit testily. “He could’ve told me the sky was purple, and I would’ve been like, ‘Hmm, okay.’ I had irons in every fire at that point.”

“And I didn’t, so I would call him out on things,” Missi said. She suddenly sounded very sad. “But I kept letting him come back.”

On May 17, 2017, Richie Tailor left the townhouse he shared with his new girlfriend, Dorie, to have dinner with his brother and sister-in-law. Dorie was idly scanning through pictures on the iPad Richie had left behind when she saw one that brought her up short. It was a screenshot of an Instagram post showing a man in a hospital bed. “A BIG THANK-YOU for everyone’s prayers and support … Should be out of the hospital Monday,” the caption read. The name on the account was “Derek M Allred.” “I was like, ‘Heck, that’s Richie,’ ” Dorie told me. When she googled Derek Allred (an alternative spelling he sometimes used), she found the trove of news stories and mug shots. Suddenly, all those fraudulent charges that kept cropping up on her credit cards made sense.

Dorie printed out the articles and brought them to the police department in The Colony, the small town outside Dallas where she lived. “I thank God to this day that it was a female officer that took my statement,” she said. “She took it seriously.” While Dorie waited to hear if the police came up with any leads, she scoured the internet for information about Derek. Like so many of the other victims, she stumbled on Cindi Pardini. The two women talked on the phone. “I heard about all the havoc he left behind,” Dorie told me. “I vowed that there was no way there’d be another victim after me.”

Dorie made sure to show the Colony detectives pictures of Derek in his Navy uniform, and the detectives contacted the Naval Criminal Investigative Service. Under the Stolen Valor Act of 2013, seeking profit by using phony military honors is a federal crime—which meant that NCIS could launch a multistate investigation.

After Dorie caught on to him, Derek began staying with his other girlfriend, Tracie Cunningham. But it didn’t take long for Tracie, who works at a post-acute rehab facility, to get sick of having him around all day. He was, she’d decided, entirely too whiny, constantly insisting that she drive him to the hospital for some emergency or another. “There are a lot of men out there who will get a little headache, and they think they have a massive tumor, that they’re dying,” she told me. “It’s a man thing. He had some of that. Real dramatic.”

Just after Memorial Day, Tracie finally dumped him. A few hours later, while she was at work, she got a call from the NCIS agent, who told her that she’d been dating a con man. Derek hadn’t stolen anything from Tracie as far as she could tell (“except time and a little dignity”), but when she heard about the other victims, she immediately agreed to help NCIS capture him.

At the agent’s urging, Tracie sent Derek a text, taking back the breakup—“I’m sorry baby, I was hormonal!”—and made plans to give him a ride home after his next medical appointment. When Derek was ready to be picked up, Tracie alerted the NCIS officer and his team. “They hightail it over there, and I’m on my way, too, because I’m not missing this,” Tracie told me. She pulled up to the patient loading area. Through the hospital’s sliding glass doors, she spied Derek in handcuffs, flanked by two agents. “I turn on my hazards, pop out with my cellphone, start snapping pictures,” Tracie said. “The NCIS agent is like, ‘No!,’ but I’m like, ‘Oh yeah, I need pictures of this. This is for justice for other people.’ ”

With Derek finally in custody, his victims celebrated, texting one another grim fantasies about the future that awaited him in prison. NCIS agents interviewed victims around the country, whose stories bolstered the case that Derek was a habitual offender.

A few days before Christmas, Derek pleaded guilty to two counts of identity theft and one count of mail fraud, charges with a combined maximum penalty of 24 years in prison. As of press time, his sentencing hearing hadn’t yet been scheduled. His victims are hoping he’ll serve long enough that he’ll come out an old man, less able to flirt his way into women’s bank accounts.

In the meantime, they continue the slow work of putting their lives back together. Missi has finally gotten to the point where she can make jokes about Derek with her daughters. Linda has started tentatively dating again, after more than a year. The other day, when she was out to dinner with a guy, she peeked in his wallet, just to make sure the name he told her matched the name on his ID.

Dorie, Derek’s last victim—for now, at least—recently submitted the police report and a file of articles about Alldred to her bank and credit-card companies to clean up the financial mess he’d made. Citibank promptly reversed the $7,000 in fraudulent charges that he’d racked up on one of her cards, but Chase has refused to credit her for the $10,000 he spent on another. “They refused to refund me,” she told me, “because they said I knew the guy.” (When asked for comment, Chase said that Dorie had authorized Derek’s use of the card, and that she’d told a fraud supervisor that many of the transactions were valid.)

This past summer, I made an appointment for a video visit with Derek at the Denton County Jail, in Texas. I had so many lingering questions: Who was on the other side of the line when Derek had those hour-long conversations with his “daughter” or his “admiral”? How had he finagled his university email address and ID card? Did he have a secret stash of money somewhere? And then there was the question I imagined was unanswerable, but that I needed to ask anyway: What did it feel like to be so skilled at faking love?

I sat in the visitation room, doodling in my notebook as the appointed time came and went. I’d resigned myself to the idea that nothing was going to happen when the screen suddenly illuminated, and I saw Derek Alldred’s angular face and blunt chin, familiar from all those mug shots. He was in an orange jumpsuit, and the camera caught him at an awkward overhead angle, like an unflattering selfie. I told him I was a journalist, and he seemed unfazed. “I was going to decline the visit, but the guard said, ‘Are you sure? It’s a pretty girl,’ ” he said, flashing me a smile. By the end of our conversation, Derek said he wanted to tell his side of the story to me and only me, and promised we would talk again soon. I hung up the phone feeling a particular kind of journalistic high, an I-got-my-story cockiness.

Over the next few months, I spoke with Derek several times. He was never quite ready to reveal anything of substance in the half-hour blocks of time that the prison videophone system allotted us. He wanted to wait until a certain court date had passed, or he needed to consult his lawyer. “Two sides to every story,” he kept telling me. “Two sides.” He professed to want to be fully forthcoming with me, but our calls always seemed to get cut off at crucial moments; sometimes, he just never answered. At first, I chalked our communication difficulties up to the institutional roadblocks of prison communication, but they kept piling up.

It took me much longer than I’d like to admit to realize what I had felt that first day after I left the Denton County Jail and drove too fast past the hayfields of North Texas, singing along to Merle Haggard: that my future was sunny and full of promise, because I had met a man who was going to give me everything I wanted.